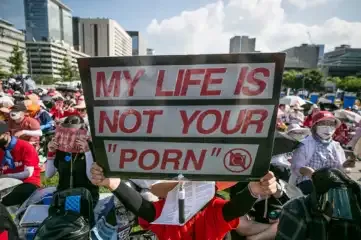

HOW FEMINISM BECAME A DIRTY WORD IN SOUTH KOREA?

The demonization

of feminist discourse and ideology in South Korea is critical impetus for young

Korean men’s embrace of misogynist attitudes for conservation politics

In his article "Why

So Many Youngsters in South Korea Disdain Woman's rights," S. Nathan Park

portrays forceful sexism among youthful South Korean men as a misinformed

discernment that men face cultural burdens in light of endeavours to "break

the discriminatory limitation." Park contends that this heightening

political current has driven the segment's hug of traditionalist legislative

issues, encapsulated by the mounting fame of moderate pioneer Lee Jun-Seok.

Nonetheless, the catalyst

for this aggregate sexism is more mind-boggling than a traditionalist reaction

to the apparent wrongness of reformist sexual orientation balance. The

defamation of women's activist talk and philosophy, supported by a

misinterpreted conviction that the term is inseparable from radicalism and

misandry, is vital to this speeding up political current reflected in Lee's

enemy of women's activist talk.

Park contends that a

predominant meritocratic philosophy supports youthful South Korean men's

resistance to women's liberation. Taken out from the verifiable battles of past

ages of Koreans, young fellows today partake in a "mutilated good

reasonableness" attached to the maverick pursuit and entrepreneur stresses

of a thorough and cutthroat instructive and work scene. Fundamental sex imbalance,

shown by measurements, for example, the sexual orientation pay hole augmenting

from 34.6 per cent in 2018 to 37.1 per cent in 2019, is subverted when seen

through a meritocratic point of view, "where the poor are at fault for

their anguish." Likewise, Park takes note of those youthful Korean men

overpowering support the assertion, "ladies acquire less because they give

less work to their professions."

Therefore, Park contends

the ebb and flow sexist tide is roused by youthful Korean men's view of ladies

as "dangers who keep on getting particular treatment." Regardless of

the World Monetary Discussion positioning South Korea 115th out of 149 nations

on Sex Uniformity in 2018, cultural endeavours to battle sexual orientation

disparity are understood as establishing a correctional climate for youngsters.

This predicates, like Park, contends, men's discernment that they are

"casualties of woman's rights."

Nonetheless, a

meritocratic survey of the "meeting point of sex and force" isn't

sufficient to represent the hug of forceful sexism showed by such huge

companions of youthful Korean men. Women's activist talk advances antagonism

and dread in youthful Korean men since it has been misjudged as innately

revolutionary and misandrist.

The slander of women's

activist talk and philosophy in South Korea is a basic impulse for youthful

Korean men's hug of sexist mentalities and traditionalist governmental issues.

In his article "Why

So Many Young fellows in South Korea Disdain Woman's rights," S. Nathan

Park portrays forceful sexism among youthful South Korean men as a confused

discernment that men face cultural impediments in light of endeavours to

"break the unattainable rank." Park contends that this heightening

political current has driven the segment's hug of moderate legislative issues,

encapsulated by the mounting prevalence of traditionalist pioneer Lee Jun-Seok.

Notwithstanding, the

force for this aggregate sexism is more perplexing than a traditionalist

reaction to the apparent wrongness of reformist sex balance. The disparagement

of women's activist talk and philosophy, supported by a confused conviction

that the term is inseparable from radicalism and misandry, is key to this

speeding up political current reflected in Lee's enemy of women's activist

talk.

Park contends that a

predominant meritocratic philosophy supports youthful South Korean men's

resistance to woman's rights. Taken out from the verifiable battles of past

ages of Koreans, youngsters today partake in a "misshaped moral

reasonableness" attached to the maverick pursuit and entrepreneur stresses

of a thorough and cutthroat instructive and work scene. Fundamental sexual

orientation imbalance, demonstrated by insights, for example, the sex pay hole

extending from 34.6 per cent in 2018 to 37.1 per cent in 2019, is sabotaged

when seen through a meritocratic viewpoint, "where the poor are at fault

for their misery." Appropriately, Park noticed that youthful Korean men

overpowering embrace the assertion, "ladies procure less because they give

less work to their professions."

Subsequently, Park

contends the flow sexist tide is propelled by youthful Korean men's view of

ladies as "dangers who keep on getting particular treatment."

Notwithstanding the World Monetary Gathering positioning South Korea 115th out

of 149 nations on Sexual orientation Equity in 2018, cultural endeavours to

battle sex disparity are interpreted as establishing a reformatory climate for

youngsters. This predicates, like Park, contends, men's discernment that they

are "casualties of woman's rights."

Be that as it may, a

meritocratic survey of the "meeting point of sex and force" isn't

sufficient to represent the hug of forceful sexism showed by such enormous

companions of youthful Korean men. Women's activist talk advances antagonism

and dread in youthful Korean men since it has been confused as innately

extremist and misandrist.

Online people groups

upholding ladies' privileges have prompted a developing misconception that

women's liberation is omnipresent with misandry. The Korean site Megalia was

established to battle and mirror unavoidable sexism by giving an online

discussion where ladies could air comparatively critical remarks toward men. A

heightening fanatic culture of misandry prompted the webpage to be more than once

closed down, with this more extreme talk inclining toward different sites and

online networks. Dispatched in 2016, splinter site Woman highlights present

guaranteeing on have carried out violations against men.

Met for The Korea Times,

scientist Lee Na-mi stresses that the "bounce back marvel" epitomized

by such sites, in counter to misanthropic destinations like Ilbe Stockpiling,

hazards the women's activist development being "misshaped and saw

wrongly." This is repeated by Korean women's activist YunKim Jiyoung, who

reveals to Bad habit that "women's activists are being introduced as

misandrists to be quieted and to have their endeavours for sex correspondence

derided." This is despite Woman’s teaching indicating that its individuals

don't characterize themselves as women's activists. The selfless mission for

sex fairness chances being imperilled by extremist talk that isn't illustrative

of women's activists' development for sexual orientation balance.

The impacts of such

disparagement showed in 2018 when performer San E delivered his tune

"Women's activist," covered with misanthrope verses. He followed this

with an enemy of women's activist upheaval during a show, shouting "Woman

is poison. Women's activist, no. You're a psychological sickness." His words

distort women's liberation as being inseparable from these extreme

developments.

The ramifications of the

developing disgrace related with women's activist talk are apparent in remarks

from 23-year-old Seoul understudy and self-broadcasted extremist women's

activist Shin Set-by, who disclosed to NBC News: "I would say it's as yet

hazardous to straightforwardly call yourself a women's activist in Korea

today." This is repeated by remarks from Seoul bistro proprietor Sira

Park, who told Bad habit: "I would prefer not to be known as a women's

activist here in Korea… there's a sure generalization and shame that

accompanies the title here."

This trashed view of

woman’s rights is repeated in the poisonous online reactions to the web-based

media posts of female famous people advancing women’s liberation. Artist

Irene’s 2018 Instagram post, highlighting the book “Kim Ji-youthful, Conceived

1982,” recognized by numerous individuals as women’s activist writing, was met

with scorching and threatening on the web reactions from male fans. “She has

practically come out as a women’s activist, and I’m presently not her fan,”

remarked one male online media client.

Disdainful responses to

famous people’s women’s activist loyalties have added to a culture where

women’s activist philosophy is disregarded and dependent upon apologies.

Performer Child Na-eun’s 2018 Instagram post, highlighting a telephone case

with the expression “Young ladies can do anything,” was comparatively censured.

After regrettable kickback drove Child to erase the past, her organization gave

an assertion dismissing her relationship with women’s activist talk, excusing

the trademark as “essentially a result of the French design mark Zadig and

Voltaire.” This defender reaction mirrors an earnest longing to disassociate

from any women’s activist informing.

How Woman’s rights Turned

into a Filthy Word in South Korea

The belittling of women’s

activist talk and philosophy in South Korea is a basic force for youthful

Korean men’s hug of sexist perspectives and traditionalist legislative issues.

How Women’s liberation

Turned into a Filthy Word in South Korea

In his article “Why So

Many Youngsters in South Korea Disdain Woman’s rights,” S. Nathan Park

describes forceful sexism among youthful South Korean men as a confused

discernment that men face cultural impediments because of endeavours to “break

the unattainable rank.” Park contends that this heightening political current

has driven the segment’s hug of traditionalist governmental issues, exemplified

by the mounting ubiquity of moderate pioneer Lee Jun-Seok.

Nonetheless, the driving

force for this aggregate sexism is more unpredictable than a traditionalist

reaction to the apparent wrongness of reformist sexual orientation

correspondence. The belittling of women’s activist talk and philosophy,

supported by a misinterpreted conviction that the term is inseparable from

radicalism and misandry, is vital to this speeding up political current

reflected in Lee’s enemy of women’s activist talk.

Park contends that a

predominant meritocratic philosophy supports youthful South Korean men’s

resistance to woman’s rights. Eliminated from the recorded battles of past ages

of Koreans, youngsters today partake in a “contorted good reasonableness”

attached to the maverick pursuit and industrialist stresses of a thorough and

serious instructive and business scene. Foundational sexual orientation

imbalance, demonstrated by measurements, for example, the sex pay hole

enlarging from 34.6 per cent in 2018 to 37.1 per cent in 2019, is subverted

when seen through a meritocratic viewpoint, “where the poor are at fault for

their affliction.” As needs are, Park, takes note of those youthful Korean men

overpowering embrace the assertion, “ladies procure less because they give less

work to their professions.”

Thusly, Park contends the

flow sexist tide is persuaded by youthful Korean men’s impression of ladies as

“dangers who keep on getting special treatment.” Regardless of the World

Monetary Gathering positioning South Korea 115th out of 149 nations

on Sexual orientation Balance in 2018, cultural endeavours to battle sex

imbalance are understood as establishing a correctional climate for young

fellows. This predicates, like Park, contends, men’s insight that they are

“casualties of woman’s rights.”

Nonetheless, a

meritocratic survey of the “meeting point of sex and force” isn’t sufficient to

represent the hug of forceful sexism showed by such huge partners of youthful

Korean men. Women’s activist talk advances antagonism and dread in youthful

Korean men since it has been misinterpreted as intrinsically revolutionary and

misandrist. Partaking in this article? Snap here to buy in for full access.

Just $5 per month.

Online people groups

upholding ladies’ privileges have prompted a developing misconception that

women’s liberation is universal with misandry. The Korean site Megalia was

established to battle and mirror unavoidable sexism by giving an online

gathering endeavourer ladies could air comparably defamatory remarks toward

men. A raising fanatic culture of misandry prompted the webpage to be more than

once closed down, with this more extreme talk inclining toward different sites

and online networks. Dispatched in 2016, splinter site Woman highlights present

guaranteeing on have perpetrated wrongdoings against men.

Met for The Korea Times,

specialist Lee Na-mi stresses that the “bounce back wonder” epitomized by such

sites, in reprisal to sexist destinations like Ilbe Stockpiling, hazards the

women’s activist development being “misshaped and saw wrongly.” This is

repeated by Korean women’s activist YunKim Jiyoung, who discloses to Bad habit

that “women’s activists are being introduced as misandrists to be quieted and

to have their endeavours for sex balance vilified.” This is regardless of Woman’s

precept determining that its individuals don’t characterize themselves as

women’s activists. The unselfish mission for sex equity chances being

endangered by revolutionary talk that isn’t illustrative of women’s activists’

development for sexual

The impacts of such

derision showed in 2018 when performer San E delivered his melody “Women’s

activist,” covered with sexist verses. He followed this with an enemy of

women’s activist upheaval during a show, shouting “Woman is poison. Women’s

activist, no. You’re a dysfunctional behaviour.” His words distort women’s

liberation as being inseparable from these extreme developments.

The ramifications of the

developing shame related to women’s activist talk are clear in remarks from

23-year-old Seoul understudy and self-announced extremist women’s activist Shin

Set-by, who revealed to NBC News: “I would say it’s as yet risky to

straightforwardly call yourself a women’s activist in Korea today.” This is

emphasized by remarks from Seoul bistro proprietor Sira Park, who told Bad

habit: “I would prefer not to be known as a women’s activist here in Korea…

there’s a sure generalization and disgrace that accompanies the title here.”

This defamed view of

women’s liberation is repeated in the disdainful online reactions to the

web-based media posts of female superstars advancing woman’s rights. Vocalist

Irene’s 2018 Instagram post, highlighting the book “Kim Ji-youthful, Conceived

1982,” recognized by numerous individuals as women’s activist writing, was met

with blistering and antagonistic online reactions from male fans. “She has

essentially come out as a women’s activist, and I’m as of now not her fan,”

remarked one male online media client.

Scornful responses to

VIPs’ women’s activist loyalties have added to a culture where women’s activist

philosophy is disregarded and dependent upon apologies. Performer Child Na-Eun’s

2018 Instagram post, highlighting a telephone case with the expression “Young

ladies can do anything,” was likewise censured. After a bad backfire drove

Child to erase the past, her organization gave an assertion dismissing her

relationship with women’s activist talk, excusing the trademark as “essentially

a result of the French style mark past and Voltaire.” This defender reaction

mirrors a pressing craving to disassociate from any women’s activist informing.

The counter women’s

activist language utilized by traditionalist pioneer Lee Jun-Seok, whom Park

sees as the “political boss” of sexist young fellows, is obliged to the

multiplication of the legend that revolutionary, misandrist developments are

characteristically connected with women’s liberation. In his book, “Reasonable

Rivalry: Requesting Worth and Future from Korea’s Traditionalism,” Lee

recognizes; “Where it counts in their souls, I figure moderate women’s

activists would have blended inclinations toward Woman.” Be that as it may,

this concession summons a proceeded with a wariness of the women’s activist

development by recommending its place of contrast with revolutionary misandrist

developments is negligible.

Thusly, Lee’s correlation

of Woman to “psychological oppressors” serves to multiply, abuse, and boost

cultural misconception of women’s liberation. This methodology supplements his

plans represent considerable authority in disbanding measures that advance

sexual orientation equity, such as promising to annul female portions in his

gathering, Individuals Force Gathering (PPP). Since Lee’s language is

established in an assault on extremist women’s liberation, a comprehension of

the disgrace emerging from Korean culture’s disarray of woman’s rights with

these extreme developments is pivotal to investigating how his political

decision as head of the PPP has accrued the support of misogynist young men.

Stigmatized public

perception of feminist ideology, understood to be permeated with misandry and

radical feminism, underpins young Korean’s men’s perception of themselves as

“victims of feminism.” Alongside contributing factors such as the demographics’

“worship of the idea of meritocracy,” the demonization of feminism is critical

to understanding the “over-the-top hostility” toward this discourse, which Park

contends is central to young men’s embrace of conservatism.